Everyone seems to have an opinion on watering cotton in humid regions- do this, don’t do that unless this happens, etc. Even when you do everything right in a normal year, dryland cotton in TN often comes out close (and occasionally ahead) of irrigated. In a normal year, cotton often finds its way into the more droughty areas of the farm and is often bumped out from under pivots to make way for corn or soybeans which typically respond better to irrigation. Unfortunately, it looks like our response to irrigation during 2022 will more closely mirror that of TX or AZ than what we’ve seen in TN during the past few years. Still, there are a few important things to keep in mind to maximize the response of cotton to irrigation. In this blog, Dr. Avat Shekoofa and I have compiled a few of our ‘dos and don’ts’.

Everyone seems to have an opinion on watering cotton in humid regions- do this, don’t do that unless this happens, etc. Even when you do everything right in a normal year, dryland cotton in TN often comes out close (and occasionally ahead) of irrigated. In a normal year, cotton often finds its way into the more droughty areas of the farm and is often bumped out from under pivots to make way for corn or soybeans which typically respond better to irrigation. Unfortunately, it looks like our response to irrigation during 2022 will more closely mirror that of TX or AZ than what we’ve seen in TN during the past few years. Still, there are a few important things to keep in mind to maximize the response of cotton to irrigation. In this blog, Dr. Avat Shekoofa and I have compiled a few of our ‘dos and don’ts’.

Below is a brief list of pointers to maximize your return on irrigation investment when irrigating cotton.

- Overhead irrigation should not occur during the morning, as it will impact pollination. Research as far back as the 1920s (Lloyd) identified morning irrigation with reduced boll set, but Burke (2000) reported the mechanism at the Beltwide Cotton Conferences in 2000; cotton pollen is ‘hypersensitive to osmotic injury and any contact with water disrupt the pollen grains and prevented self-pollination of the cotton flowers’. Irrigate overnight if applying overhead water may limit the impact of irrigation on boll retention.

- Try to limit temperature shock while maintaining adequate levels of plant available water. My point? I’d prefer introducing cold irrigation water overnight than during the hottest part of the day, especially if it is overhead water BUT if profile gets extremely depleted, I would irrigate in the heat of the day if that’s what it took to bring the profile back closer to field capacity.

- A large, soaking application is preferred over multiple small irrigation events. Prolonged periods of soil and/or canopy saturation are not desirable. The plant root is able to function best when the soil has partially drained and part of the pore space is partially occupied by air. Multiple, small irrigation events will result in more water lost to evapotranspiration and if irrigating overhead, will keep the canopy wet for a longer period. This is also not desirable from a disease management standpoint. This point is particularly troublesome in West Tennessee, since many fields won’t allow an application larger than 0.4” before unacceptable levels of runoff are generated. Cover crops can help increase this amount over time, but we don’t currently have much control on infiltration rate.

- In the MidSouth, irrigation prior to bloom isn’t normally warranted . . . but 2022 appears to be different. A good portion of the 2022 crop will need irrigation during the late square stage. A relatively dry June helps cotton later in the year but we need a few rainfall events to keep the plant on-track. I’ll have a blog next week covering the target development curve from COTMAN- spoiler alert, we are likely going to fall well-below the normal/desired number of NAWF when the majority of this crop enters bloom (already seeing that now). Irrigation water prior to bloom may help increase NAWF observed at first bloom during 2022. You can read more about growth stage specific water requirements in this blog from 2020.

- Properly schedule but also use the plant as an indicator. A little wilt during the heat of the day is not a major concern as we move further into flower, but wilt early in the morning or into the evening is a sign of drought damage. During late square, plant water use under high evaporative demand and dry air is around 1.0” per week. At first bloom, water use increases to around 1.5” per week and peaks at near 2.0” per week after peak bloom. Consider these numbers as you time irrigations and watch for wilt.

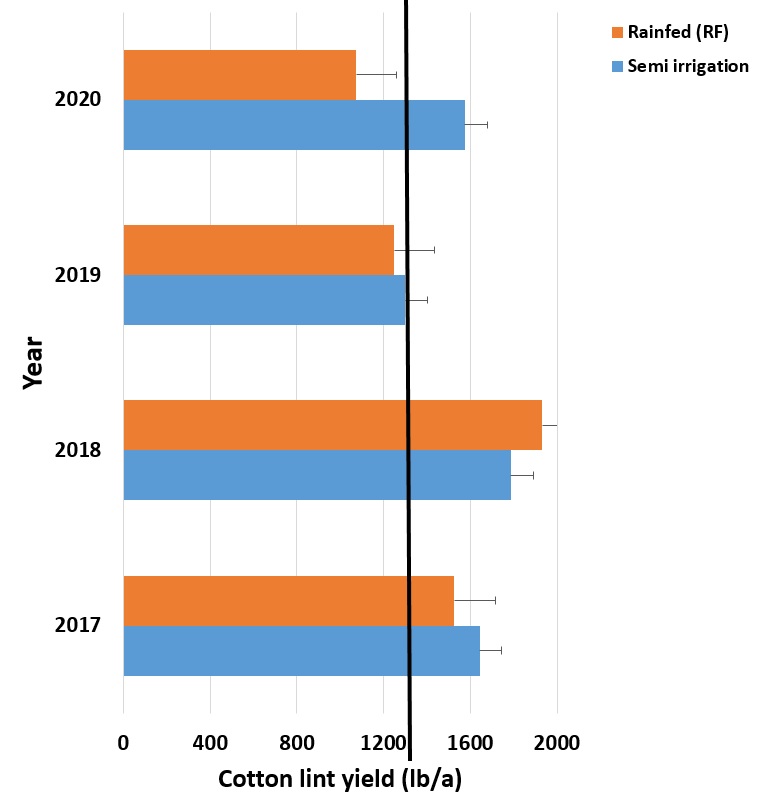

Research at the West Tennessee Research and Education Center in Jackson between 2017-2020 compared semi-irrigation (0.5″ from flower to peak flower, 1″ from peak flower to open boll) to rainfed treatments. Even in these relatively wet years, the semi-irrigated treatments out-yielded the rainfed treatments by 132 lb per acre, or 8.5% (Figure 1). Proper irrigation is critical in maximizing yield potential; field specific data is the best way to time irrigation decisions.

Today is Friday, July 8th, and it would be helpful for those of us who are sprinkler irrigating corn and soybeans to receive a similarly thorough post with irrigation management suggestions as we go forward through July and August.

On it, Mr. Jameson! Thanks for the note.