While May brought a great deal of rain, June and July have been dry for much of West Tennessee. We are already beginning to see the impacts on cotton growth and development. While we still have very good cotton yield potential, we need a good soaking rain in the coming weeks. This blog highlights impacts of drought on cotton during the growth stage, provides general information on scheduling irrigation and highlights a few scheduling methods.

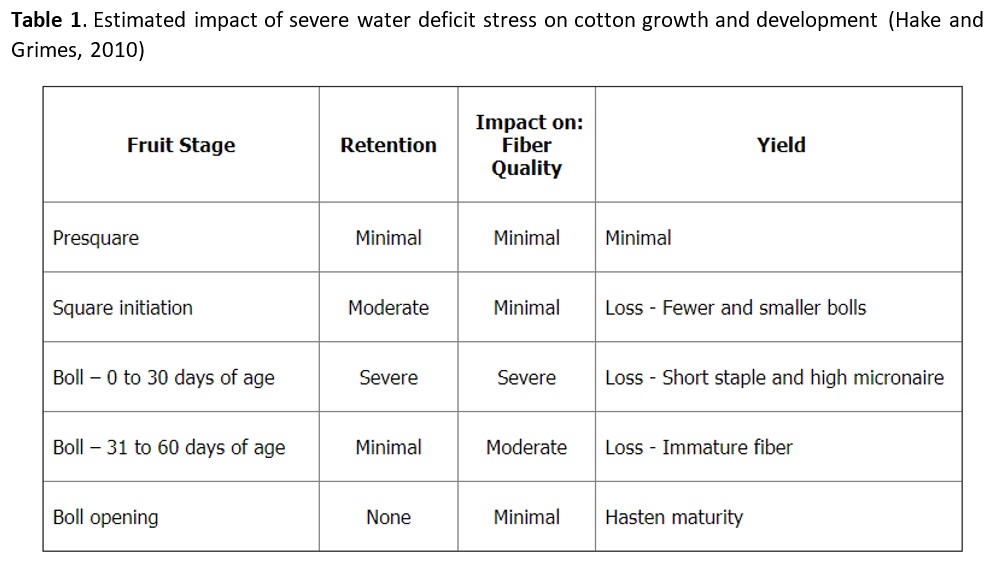

Ideally, the soil profile needs to provide sufficient plant available water throughout the blooming period. As we begin to move towards the permanent wilting point during the blooming window, fruit retention may begin to decline and maturity may be delayed. If a rainfall or irrigation event does not ameliorate the stress, yield penalties may develop. Cotton plants are particularly susceptible to drought during the early boll development stages which immediately follow flowering (Table 1). Keeping soil profile at or near field capacity at early bloom through peak bloom will support earliness and maximize yields.

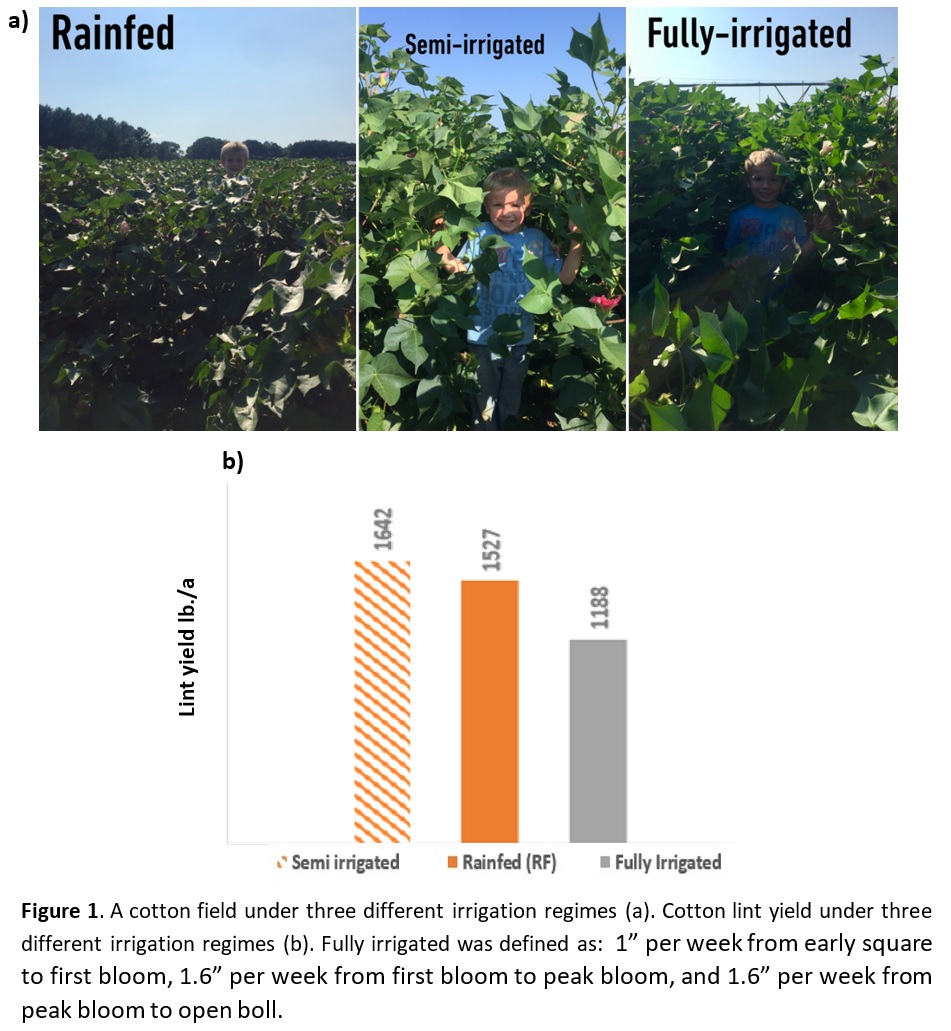

It is also important to note, however, that overirrigating can be extremely detrimental. Numerous studies evaluating irrigation regimes have been conducted at the West Tennessee Research and Education Center over the past 30 years. Within a silt loam, we have consistently seen an irrigation regime [(i.e., semi-irrigated (Figure 1)] which provides 0” per week from early square to first bloom, 0.5” per week from first bloom to peak bloom, and 1” per week from peak bloom to open boll maximize yields. Yield from the 2019 trial is included in figure 1b.

These observations are not unique to small plot research. Over the past five years, we’ve heard several complain that yields outside the pivot were similar (and occasionally greater) than areas under the pivot. Much of that penalty is likely associated with prolonged periods of saturation which reduce fruit retention and delay maturity. Ideally, our soils would allow an inch to be applied at a time; instead, irrigation events of over 0.3” often result in runoff. We are subsequently forced to run the pivot several times at 0.3” per turn to get the needed amount of water on the field. This leaves us with saturated soils over a prolonged period of time. If you are in that scenario, I would encourage you to run the pivot at night, apply as much water as possible with each application without generating runoff, and consider running an inexpensive cover crop (bin-run wheat or similar) to increase water infiltration and water holding capacity.

While we still have questions to answer concerning cotton irrigation, there are a few other points to keep in mind:

- Schedule your irrigations. There are several methods with numerous strengths and weaknesses. A short list from ‘easy’ to ‘difficult’ is included here.

a) Checkbook method. Document rainfall, estimate water holding capacity of your soil and crop water use. Simple and fairly accurate if radar detected rainfall is incorporated.

b) Checkbook plus atmometer. Gives better insight into atmospheric water demand and crop water use, but does not include any direct measure of plant available water. Measurement is generally good over a fairly large area and is easy to install and maintain. More on atmometers can be found here.

c) Soil moisture sensors. Provide an indirect measure of plant available water and help with scheduling an irrigation appropriately (Figure 2). Although, depending on type and quality, they might be expensive. A few tips on interpreting soil moisture data are included in a previous post which can be accessed here. - Maintaining adequate plant available water will reduce the impact of severe heat stress.

- Selection of less determinate cultivars may help with cotton production under rainfed/dryland and intermittent drought stress conditions or when irrigation practices are not possible. Numerous variety trials are conducted within each year; consult your local agronomist to find out which locations experienced drought stress and select from the top performers from that location when planting ‘drouthy’ acres.

Resources:

- Hake, K.D. and D.W. Grimes. 2010. Chapter 23. Crop water management to optimize growth and yield. pp.255- 264. In: Stewart, J.McD., D.M. Oosterhuis, J.J. Heilholt, and J. Mauney (Eds) Physiology of Cotton. Springer Science+Business Media

- https://cropwatch.unl.edu/2016/impacts-extreme-heat-stress-and-increased-soil-temperature-plant-growth-and-development

- https://cotton.ces.ncsu.edu/2016/06/factors-to-consider-for-irrigating-cotton-collins-edmisten/#:~:text=Although%20irrigation%20is%20most%20important,stage%20SHOULD%20NOT%20be%20neglected.&text=avoid%20yield%20penalties%20due%20to,cotton%20growth%2C%20and%202.)

- https://cropwatch.unl.edu/2016/atmometer-etgage-installation-tips

- https://news.utcrops.com/2020/06/why-irrigation/

- https://www.mississippi-crops.com/2016/05/24/utilizing-moisture-sensors-to-increase-irrigation-efficiency/