Over the past few weeks, several have reported poor retention in an area just northwest of Jackson. I’ve spent several days walking some of the impacted fields- this crosses multiple growers and a substantial number of acres- and the cause is becoming more clear. The adjacent image is characteristic of retention and growth noted within the impacted area. In this blog, I attempt to describe the mechanisms that drive environmental shed, our current hypothesis on the cause of poor retention in the area just north of Jackson, and the decisions you’ll need to make if you see this on one of your farms.

Over the past few weeks, several have reported poor retention in an area just northwest of Jackson. I’ve spent several days walking some of the impacted fields- this crosses multiple growers and a substantial number of acres- and the cause is becoming more clear. The adjacent image is characteristic of retention and growth noted within the impacted area. In this blog, I attempt to describe the mechanisms that drive environmental shed, our current hypothesis on the cause of poor retention in the area just north of Jackson, and the decisions you’ll need to make if you see this on one of your farms.

Background

Fruit retention – and abscission – is determined at the base of the peduncle, in an area called the abscission zone. A balance of three main hormones- ethylene, abscisic acid, and indole acetic acid- determine the activity of this zone. In an actively growing, healthy plant, these three hormones are present in a balanced ratio. After stress, however, this balance changes. If the stress or damage is severe, shedding can occur. You’ve likely heard your consultant or an agronomist talk about the abscission zone numerous times when discussing defoliation. When a defoliant is applied, we either directly manipulate this hormonal balance with a hormonal-type product or indirectly manipulate the hormonal balance by injuring the leaf which, in-turn, increases production of the stress-response hormone ethylene. This flush of ethylene alters the hormonal balance in the abscission zone and causes the abscission layer to form.

After an insect damages a fruiting body, the plant responds by altering the hormonal balance. Retention after damage is a function of the severity of the damage and the age of the fruit; the abscission zones of small squares, medium squares, and small bolls are extremely sensitive to shifts in the hormonal balance. In contrast, large size bolls rarely shed and a white flower almost never sheds.

Fruit abortion, or shedding, is commonly blamed on insect pests, but numerous stresses can cause abortion. Prolonged periods of cloudy weather, high night temperatures, drought stress, soil saturation, rainfall/irrigation in open flowers and nutrient deficiencies can all push the plant to abort fruit. Although fruit abortion can be troublesome, it is the main reason cotton is considered to be so resilient and can be planted in areas receiving only a few inches of rainfall; when faced with stress, cotton aborts fruit in order to conserve resources and invest in another fruiting body later in the season. Unfortunately for us, we need a substantial number of bolls per plant to mature a profitable crop and we often don’t have a long enough season to allow later maturing fruiting bodies to mature.

The Facts

West Tennessee cotton suffered through excessive moisture and cold stress during early June. These conditions did not support the development of a robust, deep tap root. Evidence of this stress is still clear now (see the image directly below)- in fields I’ve walked throughout West Tennessee, taproots commonly terminate after 3-5″ or make a hard turn and run horizontal instead of vertical.

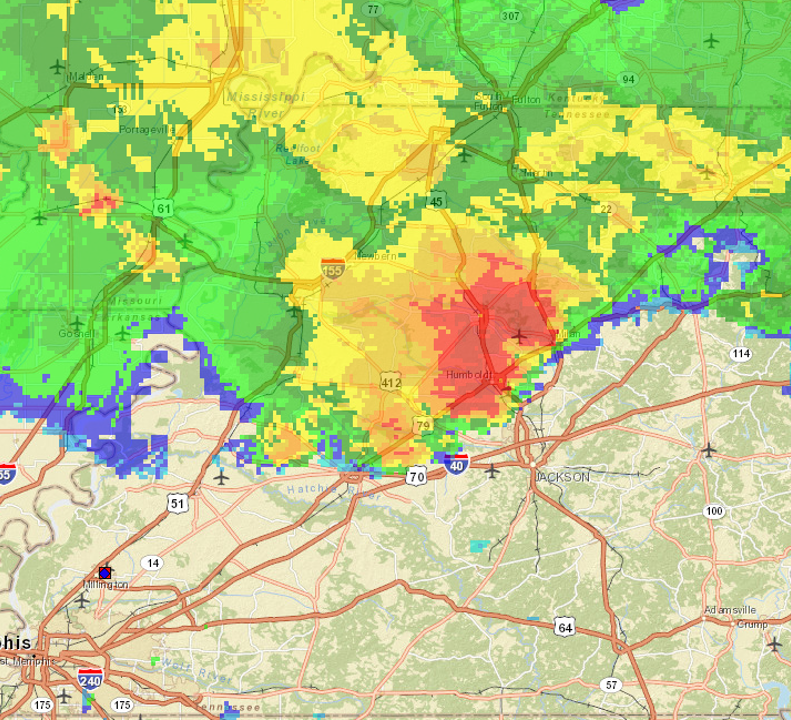

A period of very dry, hot conditions moved into the area beginning July 20th. While scattered thunderstorms provided relief to some acres, rains were best characterized as hit-or-miss with a large portion of our acres missing rain entirely. Temperatures from the 23rd of July to the 31st commonly exceeded 95F, with several 99F and one 100F observations reported in North Jackson. On the afternoon of July 31st, average temperature across West Tennessee reached approximately 97F. That evening, you may recall a strong front moved through the area. While the front moved through at approximately 60MPH, max wind speed was reported to have exceeded 70MPH by local weather stations. The largest, most structured cell formed outside of Dyersburg and ran 412. A static image of that cell at it’s peak is included below.

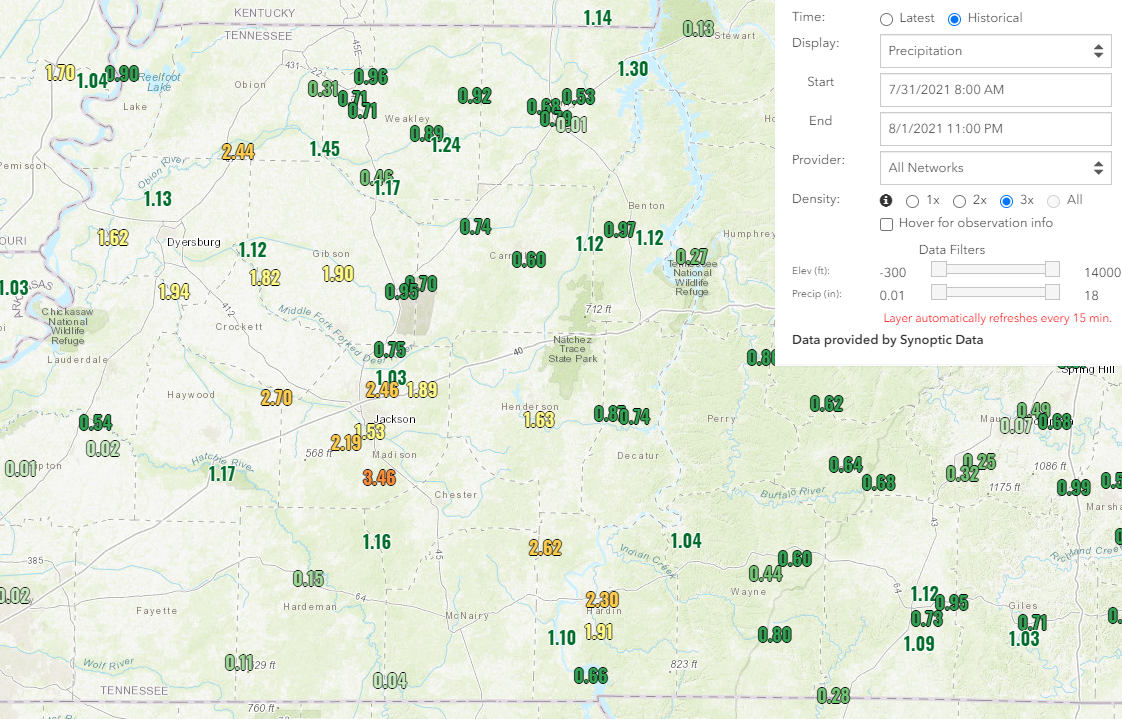

This front only gave Memphis a couple hundredths of an inch of rain and parts of Fayette approximately a tenth of an inch. However, for those under the largest cells, rainfall totals in excess of 2.5″ were reported. Again, recall that this was an extremely fast moving storm. In comparison, Hurricane Ida provided less than 2″ at the experiment station across 24 hours. Rainfall totals for the night of the 31st of July are reported in the image below.

Beginning approximately 7 days after this event, scouts began reporting low retention that could not be explained by reported plant bug numbers. The lead image on this blog represents what was commonly observed in the impacted area. Abscission of all small squares, medium size squares, and small sized bolls was reported. Furthermore, abnormal growth of sympodial branches was also noted on some plants. Most frequently, four or five first position fruit were impacted. Damage was centered around the 12th node. The potential impact of this shed was particularly concerning due to the higher than normal node of the first fruiting branch, which was a function of earlier stress endured during 2021; most plants in the impacted areas had only two or three large bolls located on fruiting branches below the aborted fruiting positions. Normal growth was noted above the impacted area, but these fruiting bodies are unlikely to mature due to the lack of remaining heat units in 2021.

The Theory

A very shallow rooted cotton crop in some areas endured a period of approximately 10 days without rain. Temperatures during this period commonly exceeded 95F. At the end of this window, a violent thunderstorm associated with rainfall in excess of 2.5″ and winds in excess of 70mph rolled through the impacted area. The physical thrashing of the drought stressed plants and hard shift from severe drought stress to saturated soil conditions generated a substantial flush of ethylene. Due to the severity of the damage and response, the plants shed all fruit with sensitive abscission zones. The altered production of hormones also led to abnormal growth of some reproductive branches and axillary buds.

Next Steps

Due to the late nature of our TN crop and the timing of the storm, the chances of the plant adding and maturing fruiting bodies to fully compensate for the lost fruit are low. Everyone’s situation is different- but I would definitely be tempted to continue managing bugs for another 10 days to give the plant a chance. The good news is the photosynthetic factory is there and appears to be in decent shape. Late fruit seems to mature quicker than early fruit. Watch the forecast closely and be ready to apply a very stiff application of boll opener 3-4 days prior to terminating low temperatures.

If you have specific questions about issues you are observing within your area, please reach out to your local Extension Agent.