Due to the ongoing drought, I’ve recently received questions along the lines of, “how much N is still available after the prill sits on the soil surface without rain for 35 plus days?” and, “should I begin a foliar fertilizer regiment to meet plant N/K/S/B demands?” In this blog, I tackle both of these questions and share N response curves generated from Tennessee data over the past 5 years.

Due to the ongoing drought, I’ve recently received questions along the lines of, “how much N is still available after the prill sits on the soil surface without rain for 35 plus days?” and, “should I begin a foliar fertilizer regiment to meet plant N/K/S/B demands?” In this blog, I tackle both of these questions and share N response curves generated from Tennessee data over the past 5 years.

“I applied urea and it didn’t rain for a month. Will my cotton crop have the N required to make close to maximum yields?”

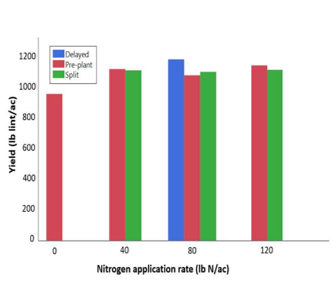

For growers that have applied 60-90 lb as urea, the simple answer is yes; the amount of soil nitrate released from the urea you applied will likely meet cotton N demand without additional N fertilizers given plant available water increases significantly in the coming week. Generally, if surface applied urea fertilizer is not incorporated into the soil, some of the N may be lost as ammonia into the atmosphere depending on weather, soil properties and management practices. So far, volatilization of surface broadcast urea in TN has likely not exceeded 30% of surface-applied urea at 120 lb N per acre. The typical recommended N rate of N is less than 120, so we would expect lower losses as ammonia. Treating urea with a nitrogen stabilizer further reduces the N loss as ammonia. Recent studies in Tennessee suggest that as little as 40 lb/N per acre is sufficient to make a 1100 lb crop. For growers that have applied ammonium nitrate, ammonium sulfate or injected UAN, there would be no significant N loss via ammonia volatilization as a result most of that N should be present in the soil. Rainfall up to this point has likely been sufficient enough to move the applied N into the soil but has not been sufficient enough to support complete uptake. If this forecast holds, nutrient uptake should be much greater in the coming weeks.

Reference: Cotton Nitrogen Management in Tennessee. 2019. Duncan L.A and T.B. Raper. UT Extension publication, W 783.“Should I apply foliar nutrients now to eliminate the deficiencies I see?”

While foliar application may provide nutrients that may not be absorbed from the soil, drought really complicates foliar fertilizer applications. Most foliar fertilizers must move across the leaf cuticle through diffusion. Unfortunately, leaf cuticles from cotton which have endured high temperatures and drought stress are much thicker and composed of harder waxes than normal. This shift in cuticle thickness and structure has been shown to reduce nutrient uptake by as much as one third. In order to compensate for these reductions in diffusion, higher rates are often considered. Unfortunately, this can increase the risk for burn as rate increases.

The risk of burn also increases with some foliar sources. Drought stressed cotton which receives an application of foliar urea, for example, will not be able to process the generated ammonium normally. As a result, ammonia toxicity and severe burn can result. This may appear as desiccated blotches or edge of leaf necrosis. While other sources may not generate this level of burn, other sources (like potassium nitrate) are often harder to find as a spray-grade or are considerably more expensive.

I’ve visited with a few concerning slow-release and other value added foliar fertilizers. Before investing in these ‘technologies’, I would encourage you to consider the mechanisms of foliar nutrient uptake. There are a variety of excellent sources of information available online, but I think one of the best is the Cotton Physiology Today series from the early 1990s. I’ve included a link to a particularly applicable article below.

https://www.cotton.org/tech/physiology/cpt/fertility/upload/CPT-July91-REPOP.pdf

At this point, I would not invest in an elaborate foliar fertilizer regime. For those that typically apply foliar boron, I would continue to do that at recommended rates. I’m not strongly opposed to small applications of foliar urea, potassium nitrate, or other ‘straight-goods’, non-value added products but I think it is very important to consider the potential of these products to provide a return on investment is lower in a drought stressed crop than in a healthy cotton crop.